Whether you are a complete beginner or regular snow-rider the risk of injury is always there. Beginners tend to fall at slow speeds and can often sustain wrist or knee injuries, whilst those of us who travel at higher velocity are at risk of injuring ourselves due to the higher forces associated with falls at speed.

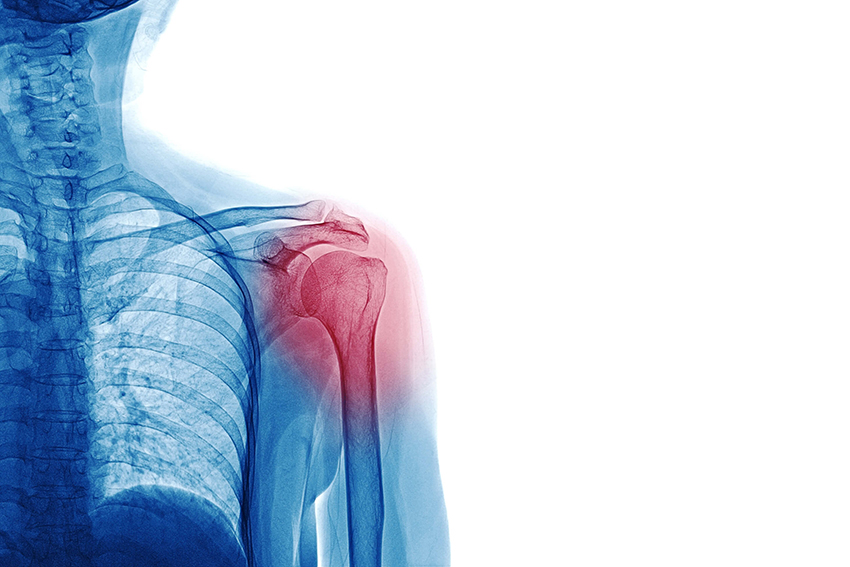

Approximately 4 to 11% of all snow sports injuries occur at the shoulder. Whilst the shoulder is the most fantastically mobile joint, what we gain in mobility we lose in stability, making it particularly vulnerable if we fall. The most common injuries include fractures, dislocations and soft tissue damage, primarily to the Rotator Cuff muscles.

Dislocation

This is when the head of the humerus bone (the ball) comes out of the glenoid (the socket) and can often happen when landing on an out stretched hand when falling. Occasionally the ball will relocate itself immediately and damage to the surrounding soft tissue is kept to a minimum. However, typically the joint will remain dislocated until the ball is relocated into the socket by a medically trained professional. If you are unlucky enough to sustain such an injury when on one of the far-flung runs at your resort this may take several hours, in which time it is likely that you will be in some pain.

If there is no associated bony injury, the damage you will sustain will be to the soft tissues and primarily the ligaments (stabilising structures) that surround the shoulder. Given that I’ve already mentioned that the shoulder is a relatively unstable joint at the best of times, damage to the ligaments can potentially lead to ongoing issues with instability and loss of function.

A short period of immobilisation and possibly the use of a sling may be recommended in the early stages whilst you get the pain under control. However, as soon as you are able to, it is important to try and mobilise the joint little and often so that the tissues and joint don’t become tight and stiff. It is also important to have the shoulder fully assessed, and sometimes imaged to ascertain the extent of any injuries. This should be followed by a course of Physiotherapy to restore movement and full function of the shoulder.

Fracture

It may be that you fall with enough force to sustain a fracture around the shoulder. This may occur around the top (or neck) of the humerus bone, or sometimes around the glenoid (socket), which is actually part of the shoulder blade. Imaging in the form of an x-ray in the first instance is required to confirm a diagnosis of a fracture. In more serious cases you may require a more detailed investigation in the shape of a CT scan.

For the majority of fractures, the healing time is around six weeks, but this can vary depending on the bone and severity of the injury. A period of immobility is very likely to be required, if not for the full six weeks then at least for a number of weeks, rather than days. This will allow the bone to heal effectively without any undue stress being placed upon it during the healing stage.

If any joint in the body needs to be immobilised for several weeks inevitably this will be associated with tightening of the surrounding soft tissues and stiffening of the joint. Once the bone has healed it may be that you require some input to restore range, strength and function but you should be advised on this by your doctor.

In terms of trying to avoid shoulder injuries on the mountains there isn’t really a lot you can do other than avoid falling over. Or just don’t go skiing or snowboarding at all. But where is the fun in that?!

Written by Ed Voss, physiotherapist